![]() “Where is the Lamb?”

“Where is the Lamb?”

Brett Kaplan

And

Isaac spoke unto Abraham his father, and said: 'My father.' And he said: 'Here

I am, my son.' And he said: 'Behold the fire and the wood; but where is the

lamb for a burnt-offering?

![]()

Bereshit 22:7 is a very subtle yet immensely powerful verse essential to the understanding of the Akedah. Abraham committed to a test whose outcome is one that all parents say is a fate worse than death; the death of one’s child. Furthermore, he was to be the dealer of the deed. Bereshit 22:7 pays testament to Isaac’s initial perplexity of his father’s uncharacteristic behavior and collection before the sacrifice. The intricacies of this difficult verse will be discovered through explanations facilitated by a non-classic commentary, a Rembrandt engraving, and an abstract Haim Gouri poem.

The non-classic commentary authored by Rabbi Yaakov Culi assists in the revealing of the subtleties contained in Bereshit 22:7. Rabbi Yaakov Culi, author of Me’am Lo’ez, lived and died between 1689 and 1732. Me’am Lo’ez is an anthology of Midrashim, Halachah, and Talmud bound together to educate the secular, or otherwise time-constrained, on the subjects of Torah.

The

commentary explains that the Torah presents us with a strange dialogue between

Isaac and Abraham:

Isaac

spoke unto Abraham his father, and said: 'My father.' And he [Abraham] said: 'Here I am, my son.'

According

to the commentary, it can be, in steps, explained as follows. Before the

Akedah, or Isaac’s birth for that matter, Abraham and Sarah sojourned in Gerar.

Abimelech, King of Gerar, nabbed Sarah from Abraham upon the pair’s arrival in

the city, for Abraham told the land’s people Sarah was his wife for fear he

would be killed for her. Abimelech and Sarah slept in bed together, though did

not touch, but God appeared in the King’s dream telling him of her marriage to

Abraham and his disallowance of touching such a woman. Abimelech reluctantly

gave Sarah back to Abraham but a short time after this event, Isaac was born.

The gossips disbelieved Abimelech did not touch Sarah and thus believed

Abimelech to be the father of Isaac; not a coincidence of G-d, Sarah, and

Abraham. Isaac was aware of these rumors.

When

Isaac realized what his father was about to do to him, he felt miserable. He

said to himself,

“Now

people will say that the rumor is true. If I were truly Abraham’s son, how

could he be preparing to kill me with his own hands?

In

other words, people will say, “If Isaac were truly Abraham’s son, how could he

have the heart to sacrifice him? No true father could do that.”

After

such monologue, Isaac spoke up and said,

“My

father…I want people to know that you are my father and I am your son. But if

you do what you are planning, who will ever believe that you are my father? I

don’t care if you kill me if it is G-d’s will. But, I am concerned that people

will use this as proof for their slander when they see you killing me with your

own hands.”

Isaac

believes that despite it being G-d’s will, the sacrifice will give rise to dire

consequences. Those that speak gossip will spread word that Isaac has got to be

the son of Abimelech. Abraham would not have the capacity to kill Isaac if he

were truly his own.

Abraham

replied to quell such fears,

“Here

I am, my son. More than anything else, this sacrifice will prove that you are

indeed my legitimate son. If you were Abimelech’s bastard, how could I have the

audacity to bring you as an offering to G-d? If a sheep has the smallest

blemish, it is unfit as a sacrifice. How can one bring a sacrifice whose very

legitimacy is blemished? People will know that G-d commanded me to offer you;

therefore, all the world will know that you are my son.”

Abraham

quashes Isaac’s worries by enlightening him that G-d does not accept blemished

sacrifices, and that if he were actually a bastard child, G-d would not accept

the sacrifice. Not relating to the passage but furthermore, if G-d wanted a

legitimate son he would have stated,

“Take

your son, your only son, whom you love, Ishmael…”

instead of declaring Isaac.

Abraham

said,

“Here

I am, my son,”

with “Hineni”. “Hineni” is the same expression Abraham used when G-d first told him to sacrifice Isaac. The term embodies more than just one’s existence but cries “I am here with all of my being, physically and spiritually, ready to do what I need to do, fully present in the moment.” Such semantic force is only repeated 22 times in the Torah, with the first three of these times contained in Bereshit 22:7. It is also uttered five times in the stories of Jacob, Esau and Joseph, and in each instance the word connotes something more than one’s mere physical presence. In this verses case, Abraham said “Hineni” as he would be fulfilling G-d’s command, and at the same time, all the world would know that Isaac was “my son.”

The

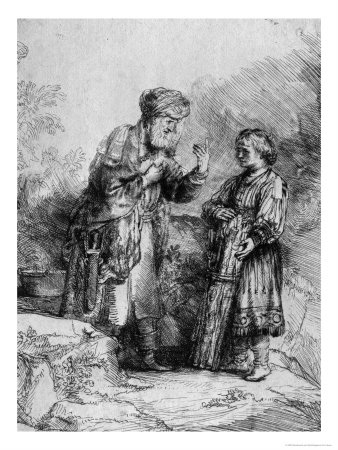

Rembrandt engraving labeled Abraham and Isaac displays a scene of strong

emotion capturing both the perplexity of Isaac and the quelling by Abraham.

Dated 1645, the piece of art hangs in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

The

Rembrandt engraving labeled Abraham and Isaac displays a scene of strong

emotion capturing both the perplexity of Isaac and the quelling by Abraham.

Dated 1645, the piece of art hangs in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

In this dramatic rendering, the pair have reached the only mountain-top surrounded by clouds. Abraham, who appears in rich, middle-eastern costume Rembrandt had invented for his patriarchs, placed the pail containing fire on the ground and turned to his son. Isaac stands in amazement and holds the bundle of wood, which he has taken from his shoulder. His eyes look questionably for the animal, which is to bleed under the slaughtering knife hanging at his father’s girdle. He asks his father, “ 'My father.' And he [Abraham] said: 'Here I am, my son.' And he said: 'Behold the fire and the wood; but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering?” Abrahams facial muscles seem to twitch in the violent effort to restrain his emotion, and with his hand pointing upwards to G-d tries to repress his son’s anxiety stating [verse 8], “My son, God will provide himself a lamb for a burnt-offering.”

Additionally, in context of the commentary, one can envision Isaac questioning the sacrifice and whether it will be viewed as legitimate. He holds the wood with a firm worry that there will only be negative repercussions as a result of following the commandment. Abraham is holding his heart with one hand and pointing to the heavens and G-d with another as if to say that he solemnly swears that both the sacrifice and Isaac being his son are and will always be legitimate. Abraham also points to the sky because his son cannot discount the fact that it is G-d’s will and G-d would not ask such a test of Abraham if Isaac weren’t his real son. His stature and position is created with a contorted face overcome with emotion, as he knows that despite him following G-d’s orders, he will lose his and Sarah’s only son.

Heritage, an abstract poem written by Haim Gouri in 1960, provides for a stronger perspective of Isaac during and after the trial. Bereshit 22:7 is a verse that displays Isaacs confusion before the sacrifice and Heritage is a poem that displays the affect the sacrifice had on the predestined child.

HERITAGE

The ram came last of all. And Abraham

did not know that it came to answer the

boy’s question – first of his strength

when his day was on the wane.

The old man raised his head. Seeing

that it was no dream and that the angel

stood there – the knife slipped from his

hand.

The boy, released from his bonds, saw

his father’s back.

Isaac, as the story goes, was not

sacrificed. He lived for many years,

saw

what pleasure had to offer, until his

eyesight dimmed.

But he bequeathed that hour to his

offspring. They are born with a knife

in

their

hearts.

Isaac, the apparently minor figure in the biblical story, is the key in Gouri’s poem and the major subject in Bereshit 22:7. Heritage accounts for Isaac’s longevity, prosperity, and fruitfulness, but also for the moment the imminent sacrifice was thwarted and transmitted to his descendants. Gouri writes,

They are born with a knife in

their hearts.

This represents the fate Jews inherited, implicitly recognized in the poem as the Holocaust and struggle for the Israeli state. In these happenings Jews had their lives destroyed despite their inscrutable trust in G-d.

In Bereshit 22:7 Isaac asks for Abraham’s attention and questions his behavior before the sacrifice, “Behold the fire and the wood; but where is the lamb for a burnt-offering?” Isaac was scarred for life atop Mount Moriah as he realized his father was willing to murder him. The verse:

The boy, released from his bonds, saw

his father’s back

is critical to the poems essence in that even though Isaac remained faithful throughout the trial, he was given the back of his father. In the Holocaust, War of Independence, and the Akedah, Jews are destroyed mentally and physically regardless of their unwavering belief in their Father, their G-d.

Bereshit 22:7 is tremendous in its value to the Akedah. Through the facilities of the Culi commentary, the Rembrandt engraving, and the Haim Gouri poem, the verses intricacies are revealed. Firstly, Isaac’s stress and confusion can be attributed to the worry that the sacrifice will not be legitimate. Secondly, Abraham’s somber mood is both strong in emotion and noticeable to Isaac. Lastly, notwithstanding Isaac being saved by G-d, he is still greatly affected by his father’s will to actually go through with the murder. The verse contains a mere 16 Hebrew words however, a lot is left to the interpretation of the studier due to the Torah’s intentional, study-inducing veil of its content.